This week opens up for the annual T’nalak Festival in South Cotabato where I am based right now. The office I work in started to get too loud with all the booming playlist on the street and the tourists idling by. It’s harder to get a tricycle anywhere, and the days will be freaking inconvenient for a socially anxious individuals like me.

Despite my preference to strive for zen in my place, I felt obliged to still take the opportunity to be in one with the provincial government. Just this morning, Dad drove me to the city to join the T’nalak Color Run 2019.

I wouldn’t have joined it if I wouldn’t be given a chance to buckle my shoes for a purpose, and with all the colored powder splashing on the road, I’m afraid to get asthma. What made me sign up for the event is that it’s a fundraiser for the people living with HIV/AIDS. While most of the countries have managed to decrease the rate of HIV infections, the Philippines’ rate is skyrocketing because of poor comprehensive sex education, lack of visibility, and homophobia and stigma attached to the dreaded disease. We’ll get to that later.

I.

I’d like to start at the finish line. I hit a 25-minute run for 5k. I was pissed off at failing to make sure my shoelaces won’t get untied on the first kilometer. I could’ve gotten a better time. Elite runners already took a turn holding their flags, and when I landed on the first station, there are no blue flags for top male runners.

The people handing out free bread and boiled eggs are my friends, so I stood there. I still thought about how to win at running when I heard someone calling me.

Running, more than a physical exercise, is an assertion of life. Suffering is central to human existence, and the pulsating heartbeats I endure with nature, under the sun or when raining sets, entail that I am still on the earth.

“Kuya,” he goes by the name Planto, 15 years old. Like a usual athlete, he shook my hands.

I remembered the guy. On the second station, we were at the same pace, but I outran him there. I grabbed a glass of water, drank half of it, and poured half of it on my head before throwing the paper cup on the bin.

“Halin pa ako Region VI,” he came as far as Region VI. Western Visayas.

“Right. Which part of Region VI?”

“Ilo-ilo.”

“Wow,” I was amused. “So who sent you here?”

“My running coach.”

“So you landed to General Santos City. Where do you stay right now?”

“Barrio Uno. Ikaw haw?”

“Esperanza. It’s eleven kilometers away from here.” He runs, I thought, so he would also appreciate how kind of far I also went. But Ilo-ilo? For a 5K? “So what’s your category really?”

“800 meters.”

“Oh, mid-range.” Planto laughed at my DOTA reference.

“My leg messed up on the middle of the race.”

“My shoelaces also messed up on the first kilometer. I had to stop. I had to sprint when I got near the cathedral.”

“I saw it. I was following you,” he said. “It’s my first time not getting any place.”

I stopped and just saw defeat on his eyes. So I tapped his shoulder and said, “You may be for sprinting, not for long runs.”

“I got a place on Milo International Marathon. In Manila.” Planto’s coach sent him there again.

“I haven’t been to Ilo-ilo, but I went to Tagbilaran a couple of months ago.” I tried to steer the topic for the heartbroken kid.

“You were there at the marathon?”

“Oh, no. Just vacation, and a seminar.” Then I remembered Tagbilaran is scary for runners because of terrible drivers and crowded roads. To run I had to settle on a boring treadmill in the hotel.

“Sige, Kuya. I have to go,” he said. “I still have a contest tomorrow in Gensan.”

“Oh, nice meeting you, Planto. Selfie muna tayo.” We went on the road where the banderitas were screaming fiesta and happiness. He asked me to add him on Facebook, but I forgot the name he uses there.

I downed my free water, and left the area too. The announcer instructed the placers to stay near the stage for the announcement. He also reminded that when all get to the finish line, they would start a foam party.

I walked away, and saw a group of runners with their bibs. “47 minutes. Wow,” one said.

The terminal for the motorycle is on the other side, so I walked past more people still on their last kilometer, walking, taking selfies, holding hands, not minding about the time they spent.

II.

Running, more than a physical exercise, is an assertion of life. Suffering is central to human existence, and the pulsating heartbeats I endure with nature, under the sun or when raining sets, entail that I am still on the earth. I thought that the organizers are wise to raise funds for HIV and AIDS by keeping the people moving.

HIV/AIDS are manageable health conditions we sweep under the rug. Sheltered in a Catholic society, I only encountered inadequate information about this in late high school to college. Talking about it comprehensively would be amiss without talking about sex. Without knowing our sexuality, it seems like the community that is supposed to nurture us would deny us of this human nature.

A lot of clinical studies of serodiscordant couples (one partner is HIV positive while the other is negative) revealed that none of the research participants were able to infect their partners with HIV even without using condoms.

Another perpetrator of stigma that exacerbates the stigma is found in our laughter. We would joke at a friend as sick with AIDS if he or she got dramatically skinny, or has any rash. Then we discourage condom use, and we chalk up the disease to homosexuality, as if the virus chooses which cells to infect.

Some companies fire people who tested positive with HIV.

For a long time, HIV treatments are not covered by some private insurances.

We spread rumors after finding out that one person has HIV.

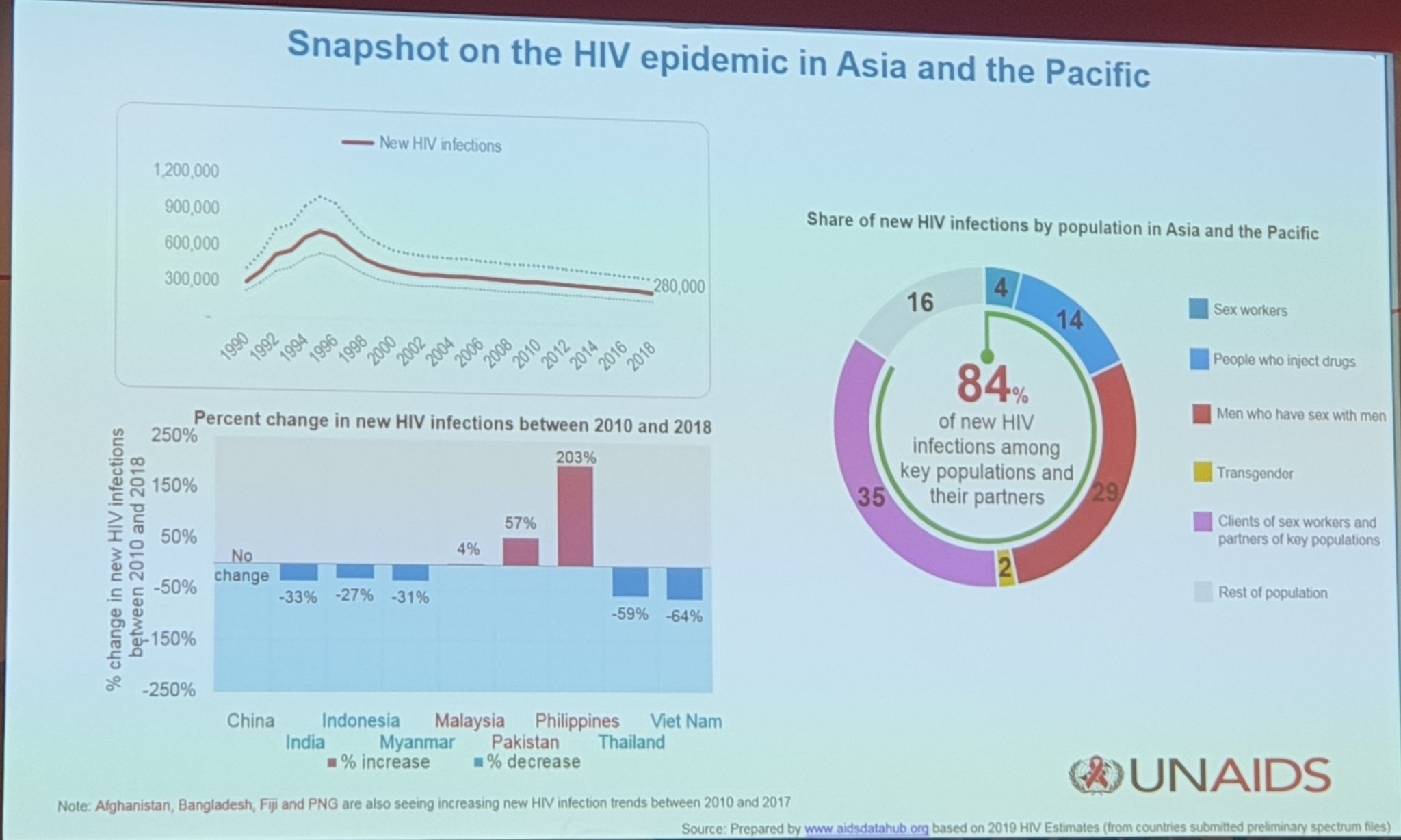

The joke’s on us, because between 2010 and 2018, our country hit a 203% increase of people living with HIV, according to UNAIDS.

With the advances in medical research, HIV/AIDS stopped being a death sentence anymore. It’s now classified under chronic illnesses, like diabetes, hypertension–illnesses that compared to HIV, are not attributed to prejudices.

But taxpayers in the Philippines, afraid of stigma, would not afford these. There are still many people who do not get tested regularly, there are only few hubs especially in small towns, and there are those HIV-positives who became drug resistant after not adhering to the free medicines given to them.

It would be a rare thing to have this read by a medical researcher or a doctor, but know that anybody can help me heighten the awareness of this misunderstood illness.

Shall we break the barrier?

Here are some facts that can help us communicate better information about HIV or AIDS:

Many of the people living with HIV, or were diagnosed with AIDS, choose to actually live healthier than those with negative status. They adhere to their medicines, exercise like a gym rat, go to work, avoid vices like smoking and binge drinking, and eat a balanced meal. What really triggers their immune system are stress and depression. There’s a Philippine Daily Inquirer article written by an HIV-positive proving this.

The thing with the U=U is sadly overlooked by dire misconception about the disease. It’s surprising that in a highly-advanced country like United Kingdom, only 19% of the population know about this. What more in the Philippines?

If people living with HIV take their antiretroviral pills religiously, their CD4 cell count will increase, and viral count will dramatically decrease. In his or her blood test, the virus can be so low that it becomes undetectable. It is a scientific fact that undetectable = untransmittable. A lot of clinical studies of serodiscordant couples (one partner is HIV-positive while the other is negative) revealed that none of the research participants were able to infect their partners with HIV even without using condoms. This scientific fact was discovered 20 years ago. Again, 20 years ago. And the U=U campaign is also supported by US Center for Disease Control (CDC), International AIDS Society (IAS), UNAIDS, and the British HIV Association (BHIVA). Anytime I discuss this with friends, they’re acting brand new.

So what is the implication of the U=U campaign? An HIV-positive partner on effective treatment shouldn’t be afraid to love and/or make love to his or her HIV-negative partner. He/she should be confident to love and/or make love with everyone (but still, love and/or make love responsibly!!!!).

The only key to be undetectable for HIV-positives is to take their medicines daily and at the same time period. It would take a while for them; it’s a case to case basis. And after being undetectable, they must still continue taking their pills.

The most important thing is this: the people who actually spread the virus are not those who are seeking treatment for HIV, but those who are HIV-positive but do not know their HIV status. So if you really care for the state of our medical condition, love yourself and get tested regularly.

What happens if someone discloses his or her HIV status to you? What should be the right thing to say? Of course, with a few visibility of people living with HIV, this is hard to imagine. But say your sibling, or your boy/girlfriend told you this?

Offer help. Treasure the fact that they are standing there with their truth. I know questions like “Who gave this to you?” and “How did you get this?” are so intriguing you wanna jump there. But these can wait, and they’re not as important than you asking them if they have sought treatment already.

If you do not know what to say, hold their hand. You better hold their hand.

Outing someone of their HIV status is a criminal act, so you should never ever gossip about them. They told you a secret because they trusted you.

There are things we think are harmless but may actually hurt them even more. Do not say “everything happens for a reason.” Wow, so should they be thanking God for the diagnosis? You are putting them in a worldview that they deserve this disease. There are people with one sexual partner but got infected with HIV; there are sexually active people that are HIV-negative.

Do not say “take care of yourself.” The fact that they disclosed this to you means they need support on their weakness. “Take care of yourself” reads “go on with your life,” “stop acting weird,” or “I’m not accountable to you.”

Do not say “you should tell your sexual partners right away.” It’s their decision who to talk to.

If someone tells me their diagnoses, I would hold their hand. This is also applicable to other conditions, like depression, cancer, or breakups.

There are two persons “cured” of HIV already. Just last week, humanized mice were cured of HIV. With these manifestations, we have many good reasons to believe that a cure for HIV is on its way.

You don’t get HIV by kissing, sharing food, drinking the same glass of water, or sharing a pool with HIV positive individuals. You don’t get HIV in parlors to get your nails done. You prevent HIV transmission by using condoms and by reducing your sexual partners.

Let’s go back to the 203% increase of HIV rate in the country. Though this is very alarming for all of us, the thing we should do is embrace this figure. It means that more people know their statuses, and they can begin to see a doctor, and love themselves. It’s more frightening to not know the truth.

I think the visibility of HIV is also problematic in many sense. Most of the narratives are about people who greatly suffered with HIV. I’m talking about Rent, Holding the Man, Angels in America, and so on. While their stories are necessary and faithfully based on the epidemic in the late 80s to early 90s, we need updating. Of course, we are not telling storytellers to tell what they do not want to tell, but consider this: didn’t you notice that the skewed representation of HIV narratives are blindsiding other equally important narratives? For a long time and until, HIV/AIDS narratives are packaged and consumed as a disease for the gays, the misfits, the sex workers, the drug addicts, the raped. And so we are more afraid of the people with HIV than the virus itself.

Aside from a subplot in How To Get Away With Murder and Season 6 and 1 of RuPaul’s Drag Race, do we have more representation about them as healthy people getting on their lives? How about in Philippine setting? When can we hold a Filipino memoir about one living with HIV?

We gladly welcome the Philippine HIV and AIDS Policy Act of 2018. Under social justice, people living with these conditions deserve this legal protection. Thank you Sen. Risa Hontiveros, and Gov. Kaka Bag-ao, and to the HIV advocates for the unparalleled efforts on raising this global concern!

The new law is just the beginning. In an article by Dr. Gideon Lasco, he did not shy away from labeling HIV as a national crisis because with the present circumstance, it really is. He unravelled several situations in the ground: the need for newer drug regimes and the option for pre-exposure prophylaxis, quality of treatment hubs and level of professionalism among practitioners, and the need for a practical sex education.

I remembered telling my colleague in a Catholic university that I may never get married and and make liberal, healthy kids because I am deeply invested in my youth advocacy, and I told her I would trade this chance to witness an HIV cure in my lifetime. I am hopeful that we are closer to that.

Thank you for a well written and interesting post. I hope for positive change in education, treatment and awareness.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you! I commit myself to this advocacy! ✊🏼

LikeLiked by 1 person

We can collectively take steps then only we can fight the disease. Kudos to you for taking an initiative for a good cause.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for reading! I am committed to help educate people about this disease and do the best that I can to help them. I am no medical practitioner but I will write for them!

LikeLike

Keep up the great work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is such a good, Kloyde! It educated me a lot. I believe if we move collectively against HIV, we can go where we wanted.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for finding this blog entry, Z. See you around!

LikeLike